A recent study promoting buying annuities has received some attention in the press.

An annuity is where you exchange some or all the money in your pension for an income. The company you buy it off will pay this income for as long as you live. You can also have the income linked to inflation and/or continue to go to your spouse if you die.

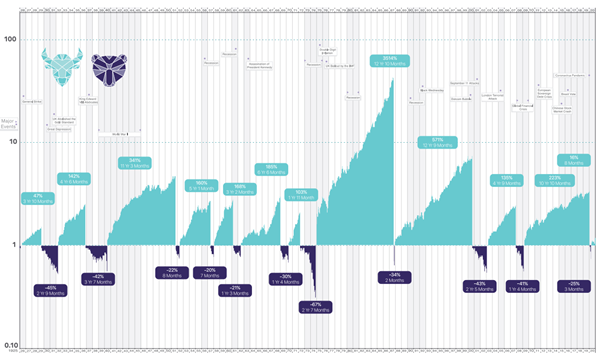

Annuities were the dominant method of getting an income from your pension. However, the sale of annuities has fallen precipitously.

This is because everyone now has the option to take how much want from their pension pots. We call this approach ‘drawdown’. One reason for its popularity is that you can leave the money to whoever you choose on your death.

What does the study suggest?

The study suggests that for the average person, sixty-seven might be the time when buying an annuity makes sense.

Does that apply to me?

The paper makes two sweeping generalisations that call the definitive nature of such a proclamation into question.

The first is that people will be more unhappy if their annual income falls in retirement than if it rises. We call this ‘loss aversion’ and a lot of evidence exists to back it up. The reality is far more nuanced. External factors such as what the income is for can have a big effect. One example might be someone using their pension to pay rent and bills. The real world and emotional consequences of not being able to pay them would be huge. Compare that to someone using the money to fund leisure expenses. Cutting back is far easier to do.

The second is people value having an income now than leaving money to loved ones later. Once again there is a lot of evidence to support this assertion for the average person. However, the opinions of our clients can widely diverge from the average.

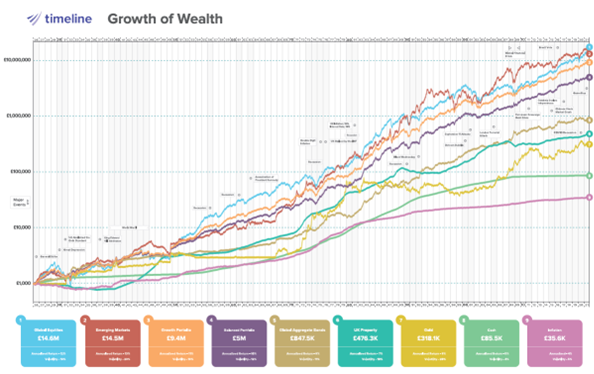

The paper acknowledges the sensitivity of their calculations to other assumptions. For example, if they change the annuity to an inflation-linked one, drawdown looks far more attractive.

The paper also looks at a hybrid approach. This is where someone buys an annuity with the non-equity element of the portfolio the pension invests into. For someone who could not tolerate the risks involved, the consequences could be ruinous.

What conclusions might I make?

Whilst the paper may not be as robust as it suggests, it highlights the importance of regularly reviewing your planning. Set and forget can be a good idea when building up a pot. The opposite is true when you come to take an income from the pot.

Constantly reappraising your planning and what you want from it is something we are well placed to deliver. We consider all the options and ensure your planning matches where you are now, not when you started taking income. Everyone is different. It is important not to make decisions based on what might be good for the average person.